Well, that’s what I’d like to think, with a nod to the famous Australian book, My Brilliant Career, by Miles Franklin.

In reply to The Retiring Sort’s Future Challenge post about second and third careers (which you can read more about here), I am much in favour of them. Gone (mostly) are the days when someone retired at a set age and expected to die a few years later of old age. People are starting new careers in their 40s, 50s, 60s and older.

It’s exciting to think, for example, that one of New Zealand’s best selling authors, Jenny Pattrick, did not have her first novel, The Denniston Rose, published until she was in her 60s. Now well into her 70s, she’s still going strong. Before she was a novelist, she had a long career as a jeweller.

The great British novelist P. D. James, now aged 92, did not have her first novel published until she was in her early 40s, and did not give up her career as a hospital administrator until she was 48.

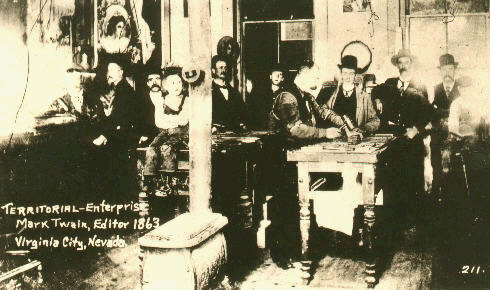

After a couple of decades as a journalist, I did a PhD in literary studies in my 40s and have worked for five years as a university lecturer in media studies.

But it’s hard to get an ongoing position in this field: perhaps harder than it is to get a full-time journalism position these days. So I could be heading for a third career—I’m thinking I might become a secondary school teacher. That would require me to get a diploma, which would take two years part-time.

What I’d most like to do, of course, is be a full-time writer, instead of having to write in my “spare” time. I’ve already had two books published and I’d dearly like to do a third. Perhaps this will be my next career. I once asked my late father, who was a dentist, what career he would choose above all others if he had the talent to do anything. He replied that he’d be a best-selling novelist, because he could be famous without being recognised in the street (debatable though in these days of modern media). Unfortunately for him, he couldn’t write fiction.

I know many people in their 50s and older who are sick of the career they have chosen—because it has changed so much, because there is ageism in it, or because there is a drive to employ cheaper staff and casuals. I urge them to think about what they would like to do, to plan for it, retrain and take up something new. It took me five years to get my PhD while working full-time for most of the duration, but I’m very glad I did it.

Even if gaining a qualification doesn’t lead directly to a job, the sense of satisfaction involved is worth its weight in gold.